Content Wars Chapter 4: The Great Gold Heist

Executive Order 6102 and the propaganda campaign that turned citizens against their own savings

1.10.2025

Imagine content used to convince the masses to sacrifice their wealth. It happened in U.S.A. in the 1930s, here’s how it went down.

The Setup: A Nation in Crisis

In 1933, America stood at the precipice of economic collapse. The Great Depression had ravaged household wealth, unemployment had reached 25%, and banks were failing at alarming rates. Into this chaos stepped President Franklin Delano Roosevelt with a radical solution that would fundamentally reshape the relationship between American citizens and their government—and it all hinged on a masterful content campaign.

On April 5, 1933, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 6102, criminalizing the private ownership of gold coins, gold bullion, and gold certificates. Americans were given until May 1 to turn in their gold to the Federal Reserve in exchange for $20.67 per ounce in paper currency. Failure to comply carried penalties of up to $10,000 in fines or ten years in prison—or both.

But how do you convince an entire nation to voluntarily surrender their hard assets—tangible wealth accumulated over generations—for paper promises from the same government institutions that had just presided over economic catastrophe?

The answer: You launch a comprehensive content war.

The Weapons: Presidential Rhetoric and Patriotic Duty

Roosevelt's primary weapon was his own voice, amplified through the emerging medium of radio. His fireside chats transformed the presidency into an intimate relationship with the American public, and he wielded this intimacy with surgical precision.

In his rhetoric, Roosevelt consistently framed the gold surrender not as confiscation, but as patriotic cooperation. The message was clear: holding onto gold wasn't a legitimate act of financial self-preservation—it was hoarding. And hoarding, in FDR's carefully constructed narrative, was fundamentally un-American.

"The blame for the present situation," Roosevelt suggested in various addresses, lay partially with those who had "hoarded" gold and currency, thereby preventing its circulation in the economy. Gold ownership transformed from a prudent hedge against instability into an act of economic sabotage.

This rhetorical sleight of hand was brilliant. By redefining gold ownership as "hoarding," the administration weaponized a term already laden with negative connotations—selfishness, greed, anti-social behavior. Citizens who simply wanted to preserve their purchasing power were recast as obstacles to national recovery.

The Distribution Network: Banks as Message Multipliers

The Roosevelt administration didn't rely solely on presidential addresses. They enlisted America's banking system as a distribution network for pro-compliance messaging.

Banks displayed posters and distributed pamphlets explaining the gold turn-in process. But these weren't merely informational materials—they were propaganda pieces designed to reinforce the administration's narrative framework. The materials emphasized:

Civic Duty: Turning in gold was presented as an act of good citizenship, comparable to military service or paying taxes

Economic Recovery: Gold surrender would enable the government to stabilize the currency and restore prosperity

National Security: Hoarding threatened not just economic recovery but the stability of the nation itself

Social Pressure: Materials implied that non-compliant citizens were harming their neighbors and community

Banks—institutions already associated with authority and financial expertise—became credibility multipliers for government messaging. When your local banker told you that surrendering gold was the responsible thing to do, many citizens believed it.

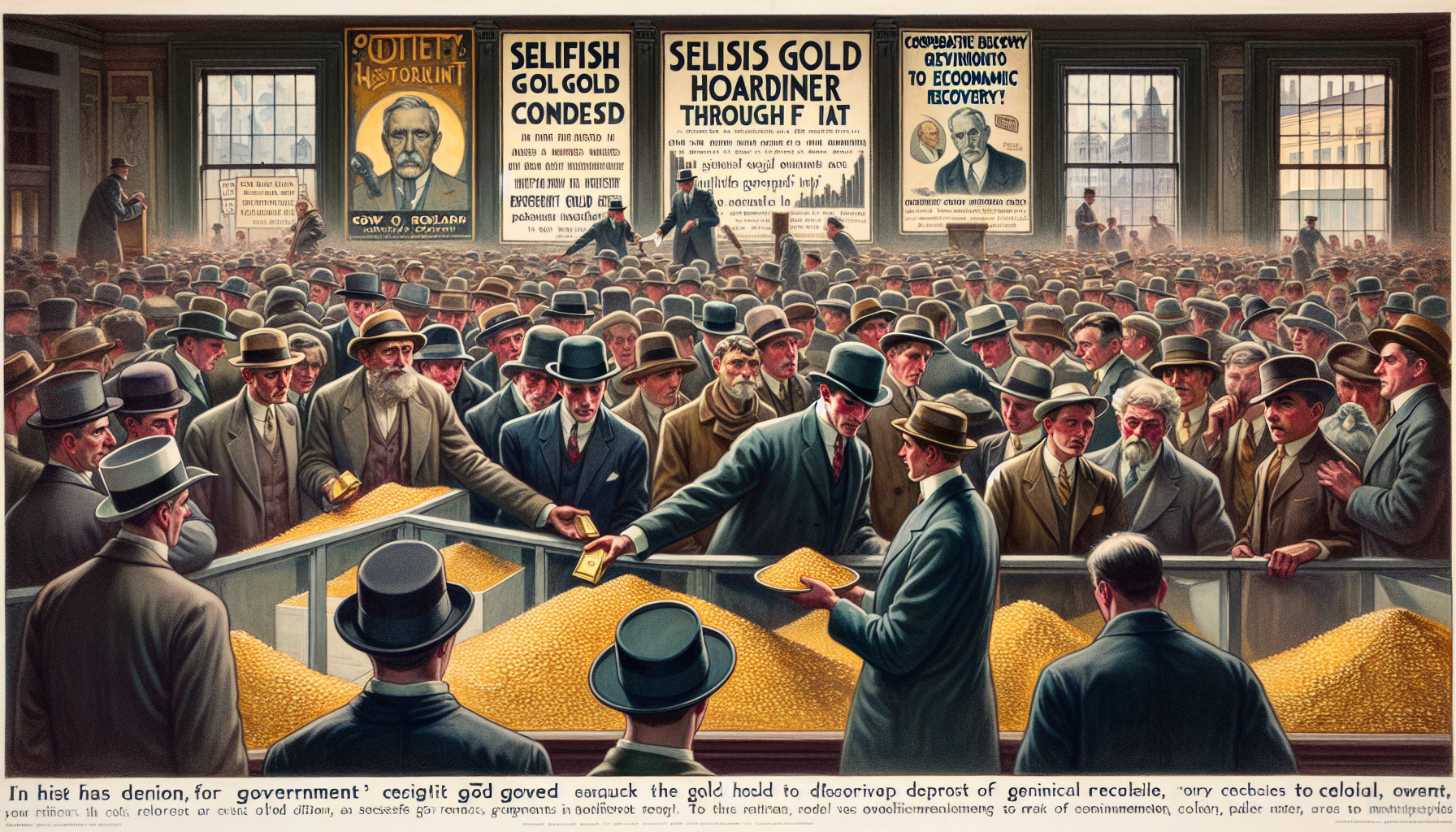

The Visual Campaign: Posters and Public Messaging

Beyond bank materials and presidential addresses, the government deployed visual propaganda throughout public spaces. Posters appeared in post offices, government buildings, and public gathering places, each reinforcing the core message: gold surrender equals patriotism.

These materials employed the visual language of patriotism—eagles, flags, strong masculine figures—to associate gold compliance with American identity itself. The implied question was devastating in its simplicity: What kind of American are you?

The messaging created a false binary: you were either a patriotic citizen helping your country recover, or a selfish hoarder prolonging the Depression. There was no middle ground, no acknowledgment that citizens might have legitimate reasons to distrust paper currency or government promises.

The Result: Compliance Through Narrative Control

The campaign worked. While exact compliance rates remain disputed by historians, the Federal Reserve accumulated significant gold reserves through the surrender program. More importantly, public resistance remained minimal. There were no widespread protests, no significant organized opposition, no political movement demanding the reversal of the policy.

The content machine had successfully reframed reality. Gold ownership—a traditional store of value and hedge against government mismanagement—became socially unacceptable. Fiat currency—paper backed only by government promise—became the responsible, patriotic choice.

Citizens complied not primarily because of enforcement threats (prosecution was actually rare), but because the narrative framework made compliance seem like the natural, obvious, moral choice. This is the ultimate goal of effective propaganda: making people want to do what you need them to do.

The Betrayal: Devaluation and Forgotten Promises

The cruelty of the campaign revealed itself less than a year later. In January 1934, Roosevelt signed the Gold Reserve Act, which immediately revalued gold from $20.67 to $35 per ounce—a 69% increase.

Read that again: The government compelled citizens to surrender gold at $20.67 per ounce, then immediately increased the official price to $35. Those who had "patriotically" complied with the surrender order had just been robbed of 40% of their gold's actual value.

The wealth transfer was massive and one-directional: from citizens to government. Those who had exchanged real assets for paper promises discovered that those promises could be unilaterally rewritten. The purchasing power of their paper currency evaporated while the government's gold reserves appreciated.

But here's what's perhaps most remarkable: there was no significant public outcry. The same content channels that had convinced citizens to surrender their gold remained silent about the devaluation's implications. The news cycle moved on. New crises emerged. The Depression continued, and Americans focused on survival rather than betrayal.

The Memory Hole: How History Forgets

Today, most Americans have never heard of Executive Order 6102. The gold confiscation—one of the most significant property seizures in American history—has been effectively memory-holed, relegated to footnotes in economic history textbooks and conspiracy theory forums.

This amnesia wasn't accidental. It was the natural result of several factors:

News Cycle Churn: As new crises emerged—continued economic struggles, the dust bowl, eventually World War II—the gold story was displaced by more immediate concerns. In the content landscape, yesterday's outrage is today's forgotten footnote.

Lack of Counter-Narrative: Those who had warned against gold surrender had been marginalized as unpatriotic or economically ignorant. After the fact, there was no credible institutional voice maintaining the counter-narrative that citizens had been betrayed.

Generational Turnover: Within two decades, the generation that remembered private gold ownership was being replaced by one that had only known fiat currency. The loss became abstract, theoretical, unmoored from lived experience.

Winner's History: Roosevelt's overall reputation as the architect of American recovery meant his individual policies—including gold confiscation—were evaluated within that positive frame. Critics looked like cranks questioning a beloved historical figure.

The Content Wars Lesson: Narrative Beats Reality

The 1933 gold campaign offers several enduring lessons for understanding content warfare:

Framing Is Everything: The same action—keeping your gold—could be framed as either prudent self-preservation or unpatriotic hoarding. Controlling the frame controlled the outcome.

Authority Multiplies Messaging: By enlisting banks and other trusted institutions as distribution channels, the government amplified its message while wrapping it in borrowed credibility.

Moral Language Defeats Rational Analysis: By casting the issue in moral terms (patriotism vs. selfishness), the campaign short-circuited rational cost-benefit analysis. Citizens who might have questioned the economic logic couldn't easily question their own patriotism.

Compliance Creates Its Own Justification: Once citizens complied, they had psychological incentives to believe they'd made the right choice. Acknowledging betrayal meant acknowledging their own gullibility—something most people resist.

Memory Is Malleable: Without continuous reinforcement, even significant historical events fade from collective consciousness. Control the ongoing narrative, and you control what's remembered.

The Modern Parallel: Content Control Endures

The 1933 gold campaign wasn't an anomaly—it was a blueprint. The same techniques continue to shape public opinion on everything from monetary policy to public health, from national security to social movements.

Today's content wars operate at greater scale and speed, but the fundamental dynamics remain unchanged: authority figures define the narrative frame, distribution networks amplify the message, moral language discourages dissent, and the news cycle ensures inconvenient memories fade.

The citizens who surrendered their gold weren't stupid or weak. They were subjected to a sophisticated, multi-channel content campaign designed by people who understood how to manufacture consent. They made the choice that seemed reasonable, patriotic, and socially acceptable within the narrative environment they inhabited.

And then they were robbed. And then they forgot.

That's the power—and the danger—of content warfare. It doesn't just change opinions; it changes reality itself, at least the version of reality that people remember and act upon.

The gold is gone. The dollars devalued. The memory faded.

But the playbook remains.

Citations and References

Emergency Banking Act, March 9, 1933, Public Law 73-1, 48 Stat. 1.

Executive Order 6102, "Forbidding the Hoarding of Gold Coin, Gold Bullion, and Gold Certificates," April 5, 1933, Federal Register.

Gold Reserve Act of 1934, Public Law 73-87, 48 Stat. 337.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. "Fireside Chat on the Banking Crisis," March 12, 1933, Miller Center Presidential Speech Archive, University of Virginia.

Bernanke, Ben S. "Money, Gold, and the Great Depression." H. Parker Willis Lecture in Economic Policy, Washington and Lee University, March 2, 2004.

Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression. 5th ed. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute, 2000.

Sumner, Scott. "The Gold Standard and the Great Depression." Mercatus Center Working Paper, George Mason University, December 2011.

Wigmore, Barrie A. "Was the Bank Holiday of 1933 Caused by a Run on the Dollar?" The Journal of Economic History 47, no. 3 (1987): 739-55.

Eichengreen, Barry. Golden Fetters: The Gold Standard and the Great Depression, 1919-1939. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Allen, Frederick Lewis. Since Yesterday: The 1930s in America. New York: Harper & Row, 1940.

content-wars-chapter-4-stealing-gold-from-citizens-1771632264425.png